Civilization: Call to Power

A better looking yet woefully dumbed-down Civ II.

Activision and MicroProse were fighting tooth and nail for the Civilization license, and the result of that struggle was Activision’s victory and a new game in the series – Call to Power, a Civ game that was developed without the guiding hand of Sid Meier. Call to Power isn’t necessarily bad so much as it’s misguided, trying to do many things all at once. Some of them work, many don’t. It seems that for every idea that Activision successfully implements (unconventional warfare, a new trade model, public works), they also manage to botch two (interface, play balance, combat model).

Activision and MicroProse were fighting tooth and nail for the Civilization license, and the result of that struggle was Activision’s victory and a new game in the series – Call to Power, a Civ game that was developed without the guiding hand of Sid Meier. Call to Power isn’t necessarily bad so much as it’s misguided, trying to do many things all at once. Some of them work, many don’t. It seems that for every idea that Activision successfully implements (unconventional warfare, a new trade model, public works), they also manage to botch two (interface, play balance, combat model).

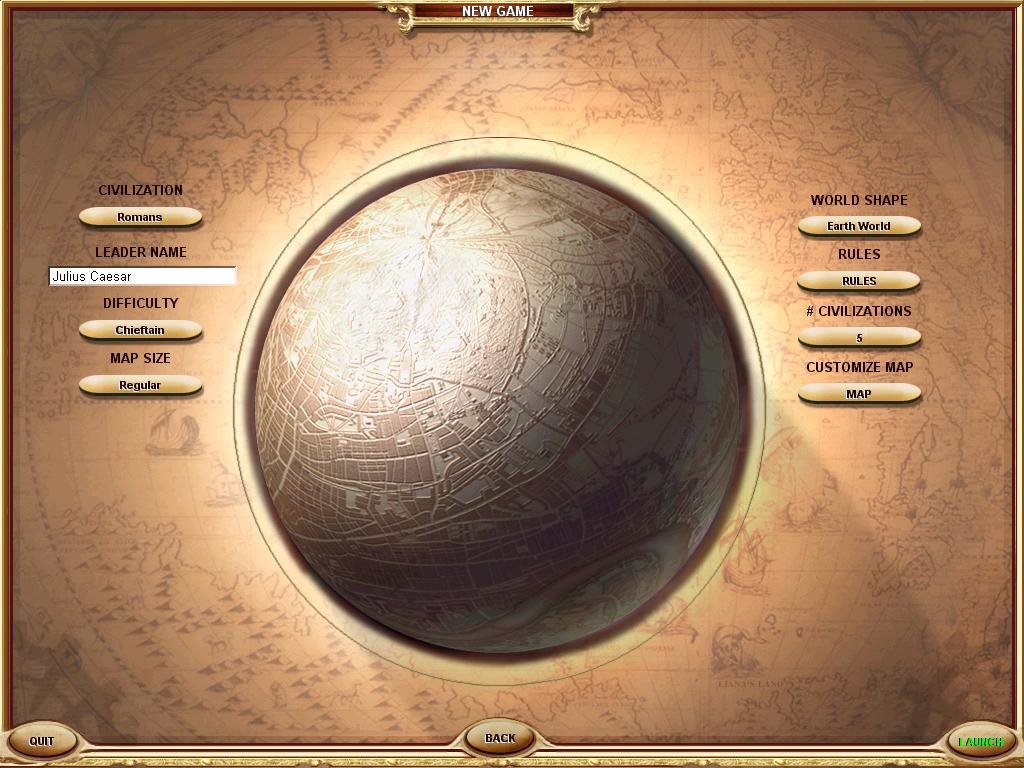

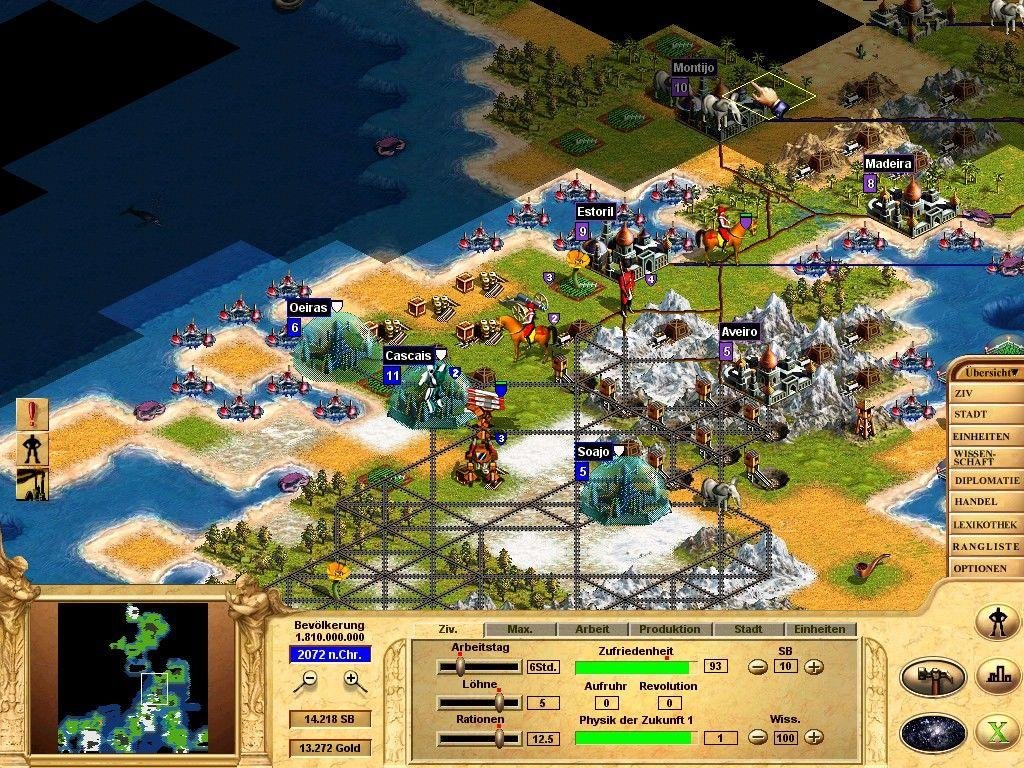

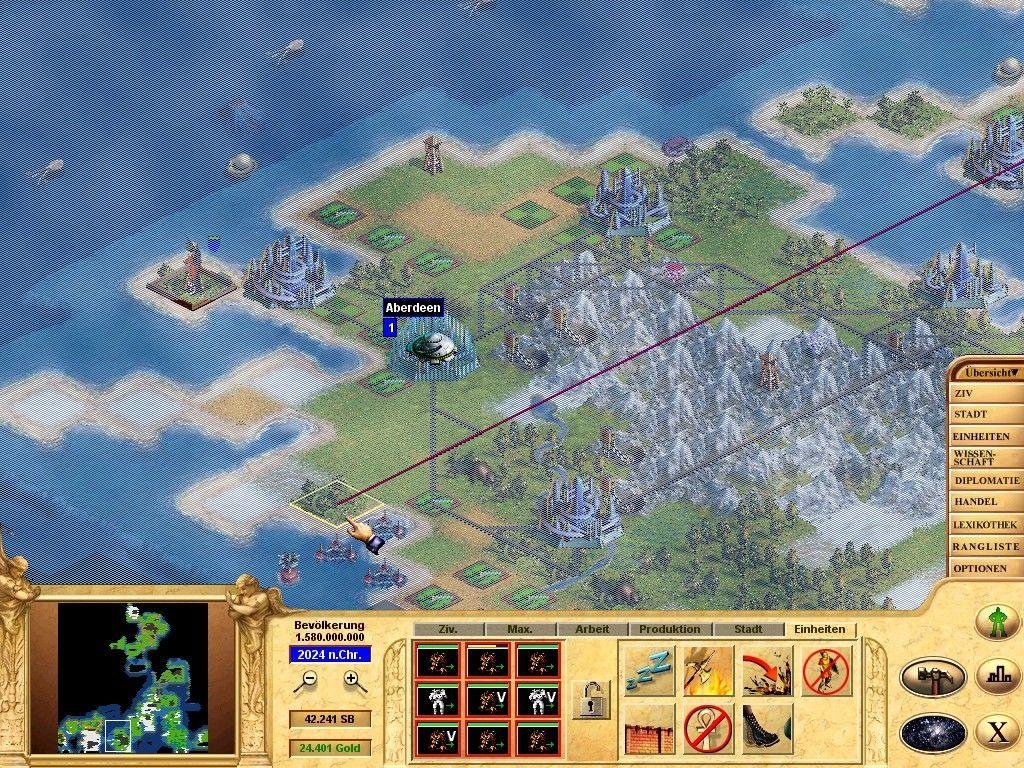

First the good. With bright clear graphics worthy of Heroes of Might and Magic III, the game looks fantastic. The maps are truly huge (talk about a long endgame). The later eras open up the seas and outer space for colonization and combat, where building and fighting are dramatically different. But Call to Power is, at its heart, Civilization II with some new ideas, not all of them sustainable within the game’s logic. Although it doesn’t share any code with Brian Reynolds’ and Sid Meier’s landmark title, that game is clearly the kernel for Call to Power.

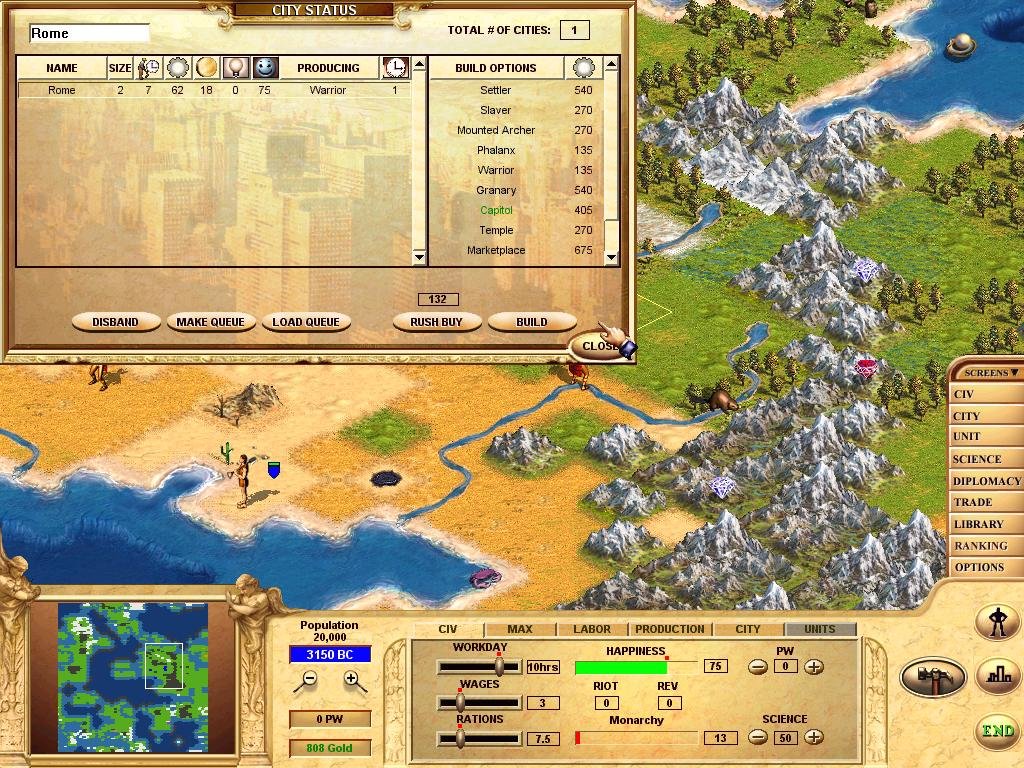

In Call to Power, all your food, production, and gold go into central coffers, where you set the rations, workday, and wages that determine your base happiness. Similarly, your units consume production for maintenance, but you can alter this by changing your level of military readiness. If you don’t anticipate a war soon, you can order your military to stand down, decreasing your maintenance costs and dropping your units to half health.

But where this federalism works best is in the game’s public works scheme. Rather than sending workers out, you divert a percentage of your production to public works. This stores up points that can be spent to improve tiles and terraform terrain. You can keep points on hand to help grow small cities with fisheries and farms. You can level entire forests or irrigate vast deserts in a few mouse clicks. Sea and space cities can thrive and quickly become productive with public works helping them along. And there’s no more trying to remember what you were going to do with that engineer after he spends four long turns cutting down a forest.

But alas, play balance went on the wayside. It’s clear Activision is unpracticed at making strategy games. For instance, consider the new super-units introduced in Call to Power. These threats arise from within your civilization, and can cripple your infrastructure quite easily. The Televangelist, for instance, can siphon your gold. The Slaver can steal your citizens, while the Eco-terrorist can pretty much decimate an entire city. There are so many potential threats, and their effects are so destructive, that you’ll spend a lot of time preparing against any and every scenario. It’s here that the game’s complexity works against itself.

But alas, play balance went on the wayside. It’s clear Activision is unpracticed at making strategy games. For instance, consider the new super-units introduced in Call to Power. These threats arise from within your civilization, and can cripple your infrastructure quite easily. The Televangelist, for instance, can siphon your gold. The Slaver can steal your citizens, while the Eco-terrorist can pretty much decimate an entire city. There are so many potential threats, and their effects are so destructive, that you’ll spend a lot of time preparing against any and every scenario. It’s here that the game’s complexity works against itself.

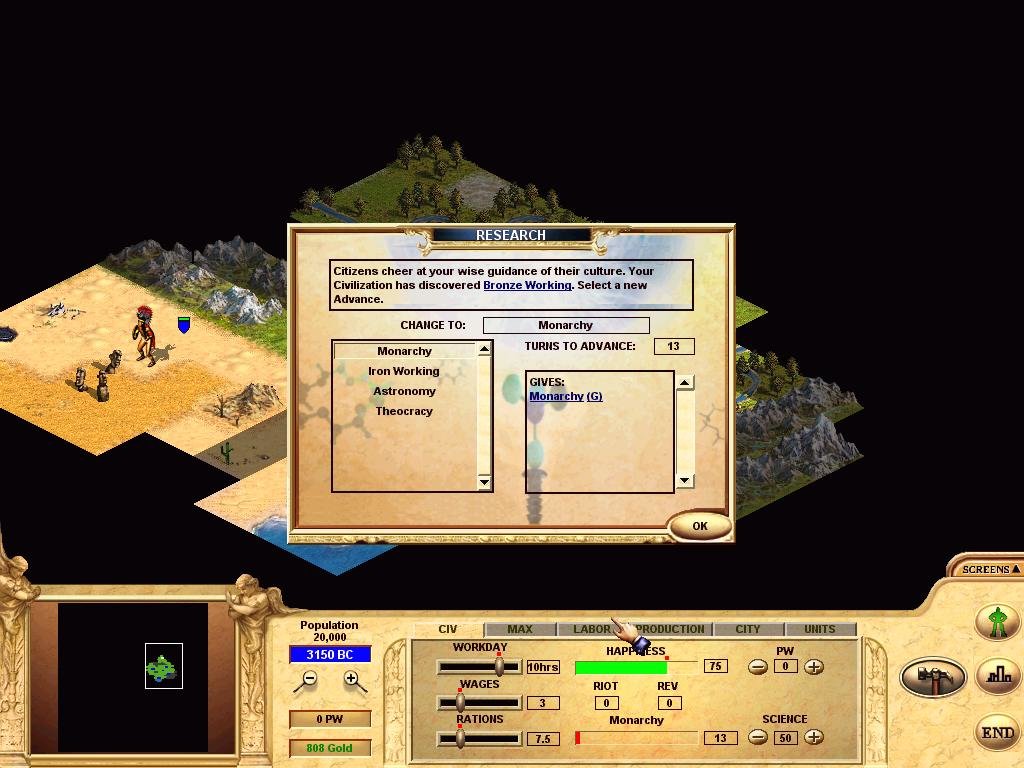

The power and pervasiveness of this kind of civil warfare means you’ll almost always have to be ready to fight two different kinds of war. It channels the gameplay through waypoints that can’t be skipped. Slavers mean you must build walls. Corporate branches and televangelists mean you must research democracy and build lawyers. The discovery of genetics and infectors means you must race to research human cloning and build microdefenses. These chokepoints shoehorn the tech tree along preset paths, limiting the game greatly.

There are hints of balance that come maddeningly close to making Call to Power as good at combat as Alpha Centauri. Defenses are particularly difficult to overcome, making entrenched growth a viable strategy (and also making unconventional warfare impossible to ignore). Units can gather in stacks of up to nine. This allows some interesting possibilities, such as balancing first strike ranged attackers with melee fighters or escorting your invaders with slavers to boost your workforce. But the stacking also highlights the gross imbalance in the combat system. Call to Power’s conventional warfare favors the number of units over the level of technology, rewarding quantity over quality.

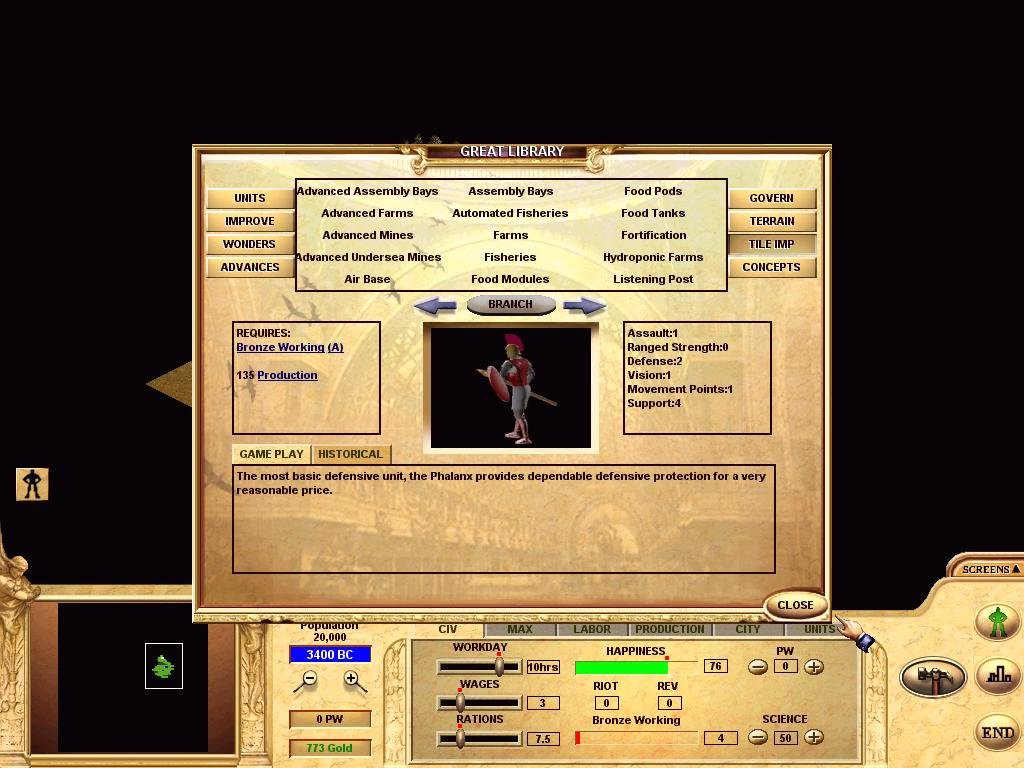

It downplays the importance of technology in warfare and t penalizes advanced civilizations. Their cheaper units are rendered obsolete, so they’re forced to build more expensive advanced units at a price out of proportion with their effectiveness. Also, it leads to some outrageous combat results that don’t jibe with what we expect from their real-world analogs. Civilization was notorious for occasional battleships sunk by phalanxes; these sorts of idiosyncrasies are rampant in Call to Power.

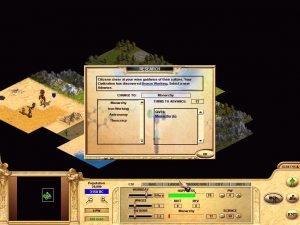

The interface presents its own problems to consider. The guiding principal in information presentation is to never take you away from the main map. To get all the details of a city, you have to click through a series of small tabs, meaning you never get a satisfying overview. Information is tucked in weird places. The autocycle and autoturn features are broken; there’s no autocenter feature to move your view with your unit selection. Different buttons and keys are required to close different types of windows.

The interface presents its own problems to consider. The guiding principal in information presentation is to never take you away from the main map. To get all the details of a city, you have to click through a series of small tabs, meaning you never get a satisfying overview. Information is tucked in weird places. The autocycle and autoturn features are broken; there’s no autocenter feature to move your view with your unit selection. Different buttons and keys are required to close different types of windows.

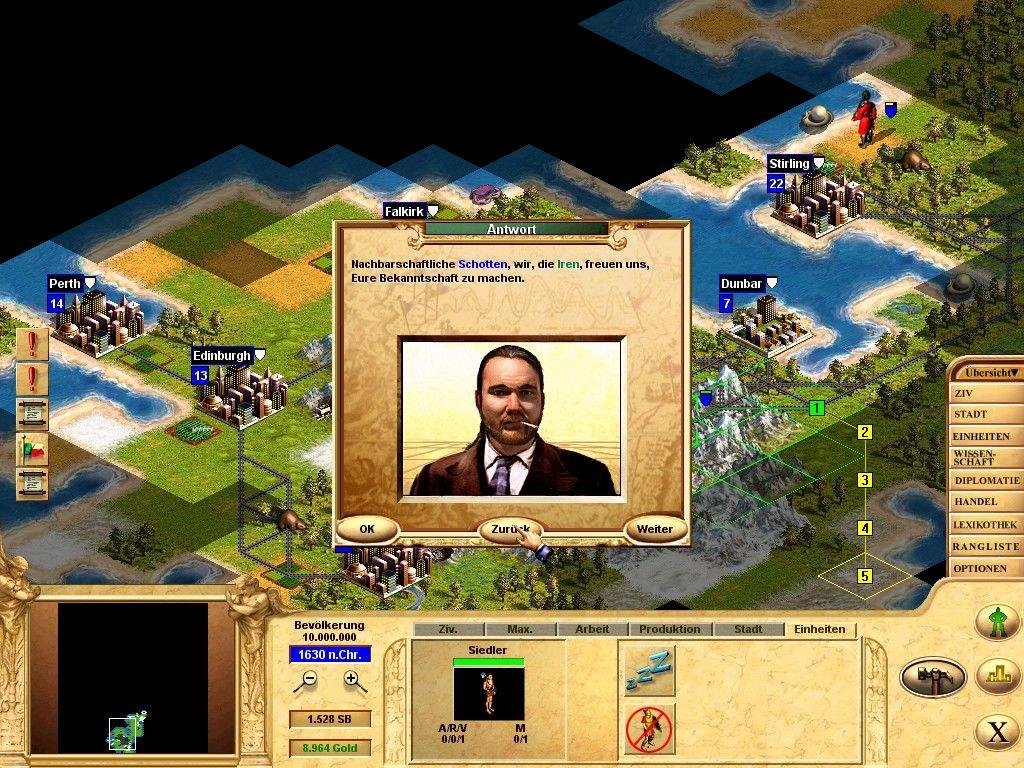

You can’t start a game during a later era in the single player games, there are no scenarios, and there’s no scenario or map editor. There are few gameplay options. And the manual is poorly writter (the Brady Games strategy guide reads more like a proper manual than the manual itself). The game also falls flat when it comes to diplomacy (Imperialism II and Alpha Centauri) and multiplayer options (no play-by-e-mail or hotseat).

Civilization: Call to Power is an ambitious attempt to follow greatness of previous Civ games, but ended up being a shallow and unbalanced mess that only pales to the quality seen in earlier games. It’s a good indication of what happens when you switch developers, going from a team who has ample experience with creating strategy games to another that has next to none.

System Requirements: Pentium II 400 MHz, 64 MB RAM, 900 MHz, Win95

-

Buy Game

www.amazon.com -

Strategy Guide

archive.org -

Vintage Website

www.activision.com

I’m extremely impressed along with your writing abilities as smartly as with the layout on your weblog. Is this a paid theme or did you modify it yourself? Anyway keep up the excellent quality writing, it is uncommon to peer a nice blog like this one nowadays.

It’s hard to come by knowledgeable people for this topic, but you sound like you know what you’re talking about! Thanks

I am really inspired together with your writing talents and also with the layout for your weblog. Is this a paid subject matter or did you customize it your self? Either way keep up the excellent high quality writing, it’s rare to peer a nice blog like this one these days.

I am extremely inspired together with your writing abilities as neatly as with the format in your weblog. Is this a paid subject matter or did you modify it your self? Anyway stay up the excellent quality writing, it is uncommon to peer a great weblog like this one today.

Hello, i think that i saw you visited my web site so i came to ?return the favor?.I’m attempting to find things to improve my web site!I suppose its ok to use some of your ideas!!

I don’t normally comment but I gotta tell thankyou for the post on this great one : D.

Cuando se nos pregunta qué clase de tiendas online frecuentamos en internet, la mayoría de nosotros respondemos las clásicas; es decir, las tiendas de ropa, por ejemplo, especialmente aquellas que venden ropa muy exclusiva que no se encuentra fácilmente en ninguna tienda de a pie; las de electrónica, videojuegos y chismes de segunda mano en general. De modo que ya lo sabe: ya sean casquillos, pasadores, ejes, tuercas cualquier otro tipo de piezas destinadas a la construcción de maquinaria lo que necesite, ahora sabe que está a un teclear y a un click de encontrar una tienda que proporcione justo lo que necesita.

I have been surfing online more than three hours today, yet I never found any interesting article like yours. It is pretty worth enough for me. In my view, if all web owners and bloggers made good content as you did, the web will be much more useful than ever before.

Hey would you mind letting me know which hosting company you’re utilizing? I’ve loaded your blog in 3 completely different internet browsers and I must say this blog loads a lot faster then most. Can you recommend a good internet hosting provider at a fair price? Thanks, I appreciate it!

I enjoy your writing style truly loving this website .

Very nice article and right to the point. I don’t know if this is really the best place to ask but do you people have any thoughts on where to employ some professional writers? Thanks in advance 🙂

Thank you for the auspicious writeup. It in fact was a amusement account it. Look advanced to more added agreeable from you! By the way, how could we communicate?

Hi there! I simply would like to give an enormous thumbs up for the nice information you’ve right here on this post. I can be coming again to your weblog for extra soon.

Hello There. I found your blog using msn. This is an extremely well written article. I’ll make sure to bookmark it and return to read more of your useful info. Thanks for the post. I will certainly comeback.

I together with my friends have been checking out the good tips located on your website then instantly I had a horrible suspicion I never thanked you for them. All the women are actually for that reason excited to read all of them and now have undoubtedly been tapping into those things. Many thanks for really being simply thoughtful and also for going for variety of excellent topics millions of individuals are really desperate to know about. Our own honest regret for not saying thanks to you earlier.

I’ve been browsing online greater than 3 hours lately, yet I never discovered any fascinating article like yours. It’s pretty worth sufficient for me. Personally, if all site owners and bloggers made just right content as you did, the net will likely be much more useful than ever before.

Undeniably believe that which you said. Your favorite justification seemed to be on the net the simplest thing to be aware of. I say to you, I certainly get irked while people think about worries that they plainly do not know about. You managed to hit the nail upon the top and also defined out the whole thing without having side effect , people could take a signal. Will probably be back to get more. Thanks

It?¦s actually a great and helpful piece of info. I am happy that you shared this helpful information with us. Please stay us up to date like this. Thank you for sharing.

You have observed very interesting details! ps nice site.

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

Very interesting subject, appreciate it for posting.

I conceive this website holds very wonderful pent subject material posts.

Very nice post. I just stumbled upon your weblog and wanted to say that I’ve truly enjoyed surfing around your blog posts. In any case I’ll be subscribing to your feed and I hope you write again soon!

I went over this internet site and I think you have a lot of good info , saved to favorites (:.

I am so happy to read this. This is the kind of manual that needs to be given and not the accidental misinformation that’s at the other blogs. Appreciate your sharing this greatest doc.

Wow! Thank you! I continuously needed to write on my website something like that. Can I implement a part of your post to my site?

I’m impressed, I need to say. Actually hardly ever do I encounter a blog that’s both educative and entertaining, and let me let you know, you will have hit the nail on the head. Your concept is outstanding; the issue is something that not enough persons are speaking intelligently about. I’m very happy that I stumbled throughout this in my seek for one thing regarding this.

I have read some good stuff here. Definitely worth bookmarking for revisiting. I surprise how much effort you put to make such a fantastic informative website.

With havin so much content do you ever run into any issues of plagorism or copyright violation? My blog has a lot of completely unique content I’ve either written myself or outsourced but it looks like a lot of it is popping it up all over the internet without my authorization. Do you know any methods to help reduce content from being ripped off? I’d truly appreciate it.

Rattling fantastic information can be found on site.

After all, what a great site and informative posts, I will upload inbound link – bookmark this web site? Regards, Reader.

What i don’t realize is in fact how you are now not actually much more neatly-liked than you may be now. You are so intelligent. You understand therefore significantly in terms of this matter, made me in my opinion believe it from so many varied angles. Its like men and women are not fascinated unless it?¦s something to accomplish with Lady gaga! Your personal stuffs outstanding. Always care for it up!

Those are yours alright! . We at least need to get these people stealing images to start blogging! They probably just did a image search and grabbed them. They look good though!

This web site is really a walk-through for all of the info you wanted about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll definitely discover it.

Thanks a bunch for sharing this with all folks you really recognize what you are talking about! Bookmarked. Please additionally discuss with my web site =). We will have a hyperlink alternate contract among us!

Pretty element of content. I simply stumbled upon your weblog and in accession capital to claim that I acquire in fact loved account your blog posts. Any way I’ll be subscribing in your feeds and even I success you access constantly fast.

You could definitely see your enthusiasm within the work you write. The sector hopes for even more passionate writers such as you who aren’t afraid to mention how they believe. Always follow your heart. “Faith in the ability of a leader is of slight service unless it be united with faith in his justice.” by George Goethals.

I’ve been browsing online greater than three hours these days, yet I by no means discovered any attention-grabbing article like yours. It¦s beautiful value enough for me. Personally, if all webmasters and bloggers made good content as you did, the internet can be a lot more helpful than ever before.

Thanks for the sensible critique. Me & my neighbor were just preparing to do a little research about this. We got a grab a book from our area library but I think I learned more clear from this post. I am very glad to see such wonderful information being shared freely out there.

Thanks a lot for sharing this with all of us you really understand what you’re speaking about! Bookmarked. Please also visit my web site =). We will have a link change agreement among us!

I got good info from your blog

Hi there! I could have sworn I’ve been to this website before but after reading through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely glad I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back often!

I?¦m now not sure the place you are getting your info, but good topic. I needs to spend a while learning much more or working out more. Thank you for fantastic info I used to be in search of this info for my mission.

Thank you for any other wonderful article. Where else could anyone get that type of information in such an ideal way of writing? I have a presentation subsequent week, and I’m on the look for such info.

I visited a lot of website but I conceive this one has got something extra in it in it

Wow! Thank you! I constantly needed to write on my blog something like that. Can I take a part of your post to my blog?

Your place is valueble for me. Thanks!…

Nice read, I just passed this onto a friend who was doing some research on that. And he actually bought me lunch as I found it for him smile So let me rephrase that: Thank you for lunch! “Remember It is 10 times harder to command the ear than to catch the eye.” by Duncan Maxwell Anderson.

of course like your website however you have to check the spelling on several of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling problems and I in finding it very bothersome to tell the truth nevertheless I will certainly come back again.

I like this web site so much, saved to my bookmarks.

You could definitely see your skills within the paintings you write. The arena hopes for more passionate writers such as you who are not afraid to mention how they believe. Always go after your heart. “We are near waking when we dream we are dreaming.” by Friedrich von Hardenberg Novalis.

Hi there! This is kind of off topic but I need some guidance from an established blog. Is it difficult to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty fast. I’m thinking about making my own but I’m not sure where to start. Do you have any ideas or suggestions? Cheers

I have been absent for a while, but now I remember why I used to love this site. Thank you, I will try and check back more frequently. How frequently you update your web site?

You have mentioned very interesting points! ps nice website .

I like what you guys are up also. Such clever work and reporting! Carry on the excellent works guys I have incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it will improve the value of my website 🙂

Can I just say what a relief to find someone who really knows what theyre talking about on the internet. You positively know find out how to carry an issue to light and make it important. Extra individuals need to read this and understand this aspect of the story. I cant imagine youre not more in style since you definitely have the gift.

entrepreneur

Hello there, I found your blog by the use of Google even as searching for a similar topic, your site came up, it appears good. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

Greetings! Very useful advice in this particular post!

This is the little changes which make the greatest changes.

Thanks for sharing!

Also visit my page – JordonIDasch

There are a handful of fascinating points with time in this post but I do not determine if them all center to heart. There’s some validity but I am going to take hold opinion until I check into it further. Very good article , thanks and now we want a lot more! Added onto FeedBurner also

of course like your website however you need to test the spelling on several of your posts. A number of them are rife with spelling problems and I in finding it very troublesome to inform the reality then again I’ll surely come again again.

Somebody essentially help to make seriously articles I would state. This is the first time I frequented your website page and thus far? I amazed with the research you made to create this particular publish amazing. Excellent job!

Good web site! I truly love how it is simple on my eyes and the data are well written. I’m wondering how I might be notified whenever a new post has been made. I have subscribed to your RSS which must do the trick! Have a nice day!

Only wanna input that you have a very decent website , I enjoy the style it really stands out.

Can I just say what a relief to find someone who actually knows what theyre talking about on the internet. You definitely know how to bring an issue to light and make it important. More people need to read this and understand this side of the story. I cant believe youre not more popular because you definitely have the gift.

Hello! I could have sworn I’ve been to this blog before but after browsing through some of the post I realized it’s new to me. Anyways, I’m definitely happy I found it and I’ll be book-marking and checking back frequently!

Hello! Do you know if they make any plugins to help with Search Engine Optimization? I’m trying to get my blog to rank for some targeted keywords but I’m not seeing very good gains. If you know of any please share. Many thanks!

WONDERFUL Post.thanks for share..more wait .. …

Have you ever thought about creating an ebook or guest authoring on other websites? I have a blog based on the same ideas you discuss and would love to have you share some stories/information. I know my readers would enjoy your work. If you’re even remotely interested, feel free to shoot me an e-mail.

Magnificent beat ! I wish to apprentice while you amend your site, how can i subscribe for a blog website? The account aided me a acceptable deal. I had been tiny bit acquainted of this your broadcast offered bright clear idea

I’m extremely impressed with your writing talents and also with the structure on your blog. Is that this a paid subject matter or did you customize it your self? Either way keep up the excellent high quality writing, it is rare to look a nice weblog like this one nowadays..

I really like your writing style, excellent information, thanks for posting : D.

I must show my appreciation to you just for bailing me out of this issue. Just after checking throughout the online world and finding methods that were not beneficial, I thought my entire life was done. Being alive without the presence of approaches to the issues you have sorted out through this article content is a serious case, as well as the ones which could have adversely damaged my entire career if I hadn’t discovered your web site. Your good skills and kindness in touching all the details was crucial. I don’t know what I would have done if I hadn’t discovered such a solution like this. I can also now relish my future. Thanks for your time very much for your high quality and results-oriented guide. I will not hesitate to propose your web page to any individual who desires direction on this problem.

You really make it seem really easy with your presentation but I find this topic to be really one thing that I believe I might by no means understand. It seems too complex and very vast for me. I’m having a look ahead in your next submit, I?¦ll try to get the grasp of it!

Hi! I know this is kinda off topic nevertheless I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in trading links or maybe guest authoring a blog post or vice-versa? My site discusses a lot of the same topics as yours and I feel we could greatly benefit from each other. If you’re interested feel free to send me an e-mail. I look forward to hearing from you! Superb blog by the way!

I loved as much as you will receive carried out right here. The sketch is attractive, your authored subject matter stylish. nonetheless, you command get got an nervousness over that you wish be delivering the following. unwell unquestionably come further formerly again as exactly the same nearly very often inside case you shield this increase.

Hello would you mind sharing which blog platform you’re using? I’m going to start my own blog in the near future but I’m having a tough time making a decision between BlogEngine/Wordpress/B2evolution and Drupal. The reason I ask is because your design and style seems different then most blogs and I’m looking for something unique. P.S Apologies for being off-topic but I had to ask!

This site is known as a walk-by way of for all of the data you wished about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll definitely uncover it.

Surprise!! Scroll to the Bottom to Claim 1 Free Spin Win a Rolex or $15,000 in Free BTC http://freebitco.in/?r=14268596&tag=scrapebox

I was reading through some of your blog posts on this website and I believe this internet site is really informative! Keep on putting up.

I have taken note of your suggestion and our address now shows on our home page above the comments

We always feel the better for a visit ; see you again soon !

I dugg some of you post as I cerebrated they were very beneficial very helpful

Simply wanna remark on few general things, The website style is perfect, the written content is real great : D.

Wow! Thank you! I permanently wanted to write on my blog something like that. Can I include a portion of your post to my site?

Good info. Lucky me I reach on your website by accident, I bookmarked it.

I truly appreciate this post. I’ve been looking everywhere for this! Thank goodness I found it on Bing. You’ve made my day! Thank you again

Excellent post however I was wondering if you could write a litte more on this subject? I’d be very thankful if you could elaborate a little bit further. Thank you!

Hi, Neat post. There’s a problem with your web site in internet explorer, would test this… IE still is the market leader and a big portion of people will miss your fantastic writing due to this problem.

I have recently started a website, the information you offer on this web site has helped me greatly. Thank you for all of your time & work.

I carry on listening to the reports lecture about receiving free online grant applications so I have been looking around for the most excellent site to get one. Could you tell me please, where could i acquire some?

Hey just wanted to give you a quick heads up. The text in your content seem to be running off the screen in Opera. I’m not sure if this is a format issue or something to do with internet browser compatibility but I figured I’d post to let you know. The style and design look great though! Hope you get the issue resolved soon. Many thanks

I simply desired to thank you so much again. I’m not certain what I would have done in the absence of these techniques provided by you regarding that concern. It has been an absolute frightful case in my position, nevertheless spending time with a new well-written mode you solved that took me to jump over happiness. I am grateful for the information and as well , sincerely hope you comprehend what a great job you are undertaking teaching others thru your websites. I am certain you’ve never encountered all of us.

Some really nice and utilitarian information on this internet site, too I think the design has great features.

I’d constantly want to be update on new blog posts on this web site, bookmarked! .

I believe this internet site has some really fantastic info for everyone : D.

Very interesting topic, thankyou for posting. “If you have both feet planted on level ground, then the university has failed you.” by Robert F. Goheen.

Wow that was unusual. I just wrote an incredibly long comment but after I clicked submit my comment didn’t appear. Grrrr… well I’m not writing all that over again. Regardless, just wanted to say fantastic blog!

Hello there, I found your blog by means of Google while looking for a related subject, your website came up, it looks great. I have bookmarked it in my google bookmarks.

Rattling nice style and great subject material, absolutely nothing else we need : D.

I have been exploring for a little for any high quality articles or blog posts on this kind of area . Exploring in Yahoo I at last stumbled upon this site. Reading this info So i am happy to convey that I’ve an incredibly good uncanny feeling I discovered just what I needed. I most certainly will make certain to don’t forget this web site and give it a glance regularly.

I like what you guys are up too. Such smart work and reporting! Carry on the superb works guys I’ve incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it will improve the value of my website 🙂

This website is known as a stroll-by means of for all of the info you wished about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse right here, and also you’ll definitely discover it.

It’s really a nice and useful piece of information. I am glad that you shared this helpful information with us. Please keep us informed like this. Thanks for sharing.

Thanks for your own labor on this web site. My niece takes pleasure in making time for internet research and it’s easy to understand why. Most people notice all about the compelling mode you present powerful suggestions via your blog and even boost participation from others on that area while my child is undoubtedly understanding a great deal. Take pleasure in the rest of the new year. You’re the one doing a first class job.

What i don’t understood is actually how you are not actually much more well-liked than you might be right now. You’re so intelligent. You realize therefore significantly relating to this subject, made me personally consider it from numerous varied angles. Its like women and men aren’t fascinated unless it is one thing to do with Lady gaga! Your own stuffs excellent. Always maintain it up!

Great ?V I should certainly pronounce, impressed with your website. I had no trouble navigating through all the tabs as well as related info ended up being truly easy to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it at all. Reasonably unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or something, website theme . a tones way for your client to communicate. Nice task..

At this time it looks like WordPress is the preferred blogging platform out there right now. (from what I’ve read) Is that what you’re using on your blog?

Very great post. I simply stumbled upon your blog and wished to mention that I’ve truly loved surfing around your blog posts. In any case I will be subscribing on your feed and I hope you write once more soon!

I really like your writing style, superb info , thanks for putting up : D.

Enjoyed looking through this, very good stuff, thankyou. “It requires more courage to suffer than to die.” by Napoleon Bonaparte.

Good – I should definitely pronounce, impressed with your site. I had no trouble navigating through all the tabs and related info ended up being truly easy to do to access. I recently found what I hoped for before you know it in the least. Quite unusual. Is likely to appreciate it for those who add forums or something, website theme . a tones way for your client to communicate. Nice task.

I got good info from your blog

I just couldn’t depart your web site prior to suggesting that I extremely enjoyed the standard info a person provide for your visitors? Is gonna be back often in order to check up on new posts

This web site is really a walk-through for all of the info you wanted about this and didn’t know who to ask. Glimpse here, and you’ll definitely discover it.

Hi my friend! I wish to say that this post is awesome, great written and come with almost all significant infos. I would like to look extra posts like this .

Very interesting information!Perfect just what I was searching for!

Awsome blog! I am loving it!! Will be back later to read some more. I am taking your feeds also

I like this post, enjoyed this one regards for posting. “To the dull mind all nature is leaden. To the illumined mind the whole world sparkles with light.” by Ralph Waldo Emerson.

of course like your web site but you have to take a look at the spelling on several of your posts. Many of them are rife with spelling issues and I in finding it very bothersome to tell the reality however I?¦ll surely come back again.

Please let me know if you’re looking for a article writer for your blog. You have some really good articles and I feel I would be a good asset. If you ever want to take some of the load off, I’d love to write some material for your blog in exchange for a link back to mine. Please shoot me an e-mail if interested. Thank you!

This is the right blog for anyone who wants to find out about this topic. You realize so much its almost hard to argue with you (not that I actually would want…HaHa). You definitely put a new spin on a topic thats been written about for years. Great stuff, just great!

I like what you guys are up also. Such intelligent work and reporting! Keep up the superb works guys I have incorporated you guys to my blogroll. I think it will improve the value of my web site :).

I’ve read some good stuff here. Certainly worth bookmarking for revisiting. I wonder how much effort you put to make such a great informative website.

keep up the superb work, I read few articles on this internet site and I think that your site is rattling interesting and contains circles of fantastic info .

excellent post, very informative. I wonder why the other specialists of this sector don’t notice this. You should continue your writing. I’m confident, you have a huge readers’ base already!

Good day! I could have sworn IÃve visited this site before but after looking at some of the posts I realized itÃs new to me. Nonetheless, IÃm certainly happy I discovered it and IÃll be bookmarking it and checking back regularly!

F*ckin’ amazing things here. I’m very glad to see your article. Thanks a lot and i’m looking forward to contact you. Will you kindly drop me a mail?

Good day! I know this is kinda off topic however I’d figured I’d ask. Would you be interested in exchanging links or maybe guest authoring a blog post or vice-versa? My website covers a lot of the same subjects as yours and I believe we could greatly benefit from each other. If you happen to be interested feel free to shoot me an email. I look forward to hearing from you! Superb blog by the way!

There is clearly a bundle to identify about this. I consider you made certain good points in features also.

Oh my goodness! Incredible article dude! Many thanks, However I am experiencing problems with your RSS. I donÃt know the reason why I am unable to subscribe to it. Is there anybody having identical RSS problems? Anyone who knows the solution can you kindly respond? Thanx!!

Pretty! This has been a really wonderful post. Thank you for supplying this information.

Thanks for some other informative site. Where else could I get that kind of info written in such a perfect approach? I have a venture that I’m simply now operating on, and I have been on the look out for such info.

Greetings! Very helpful advice in this particular post! It is the little changes that make the greatest changes. Thanks for sharing!

Really fantastic info can be found on weblog. “I don’t know what will be used in the next world war, but the 4th will be fought with stones.” by Albert Einstein.

Having read this I thought it was very enlightening. I appreciate you taking the time and energy to put this content together. I once again find myself spending a significant amount of time both reading and leaving comments. But so what, it was still worth it!

Good article. I will be going through many of these issues as well..

I like the valuable information you provide in your articles. I will bookmark your blog and check again here frequently. I’m quite certain I will learn plenty of new stuff right here! Best of luck for the next!

Would you be involved in exchanging links?

Greetings! I’ve been following your blog for a long time now and finally got the bravery to go ahead and give you a shout out from Austin Texas! Just wanted to mention keep up the good work!

Nice read, I just passed this onto a colleague who was doing some research on that. And he just bought me lunch because I found it for him smile Therefore let me rephrase that: Thanks for lunch!

Good day! I know this is somewhat off topic but I was wondering which blog platform are you using for this website? I’m getting fed up of WordPress because I’ve had problems with hackers and I’m looking at alternatives for another platform. I would be great if you could point me in the direction of a good platform.

Do you have a spam problem on this blog; I also am a blogger, and I was wanting to know your situation; we have created some nice methods and we are looking to swap solutions with others, please shoot me an e-mail if interested.

Hello, i think that i saw you visited my web site so i came to “return the favor”.I’m trying to find things to improve my web site!I suppose its ok to use some of your ideas!!

Great site you have here.. ItÃs difficult to find quality writing like yours nowadays. I really appreciate people like you! Take care!!

I loved as much as you’ll receive carried out right here. The sketch is tasteful, your authored material stylish. nonetheless, you command get got an edginess over that you wish be delivering the following. unwell unquestionably come more formerly again as exactly the same nearly a lot often inside case you shield this hike.

Very interesting subject, thankyou for putting up. “To have a right to do a thing is not at all the same as to be right in doing it.” by G. K. Chesterton.

Wonderful post! We will be linking to this particularly great article on our site. Keep up the good writing.

I was recommended this website by my cousin. I am not sure whether this post is written by him as nobody else know such detailed about my problem. You’re incredible! Thanks!

Very nice post. I simply stumbled upon your weblog and wished to mention that I have truly enjoyed browsing your blog posts. In any case I’ll be subscribing in your rss feed and I am hoping you write again very soon!

A powerful share, I simply given this onto a colleague who was doing a little bit analysis on this. And he in reality purchased me breakfast as a result of I discovered it for him.. smile. So let me reword that: Thnx for the treat! But yeah Thnkx for spending the time to discuss this, I feel strongly about it and love reading extra on this topic. If attainable, as you grow to be experience, would you thoughts updating your blog with extra particulars? It’s extremely useful for me. Large thumb up for this blog post!

Wonderful beat ! I wish to apprentice while you amend your website, how could i subscribe for a blog website? The account helped me a acceptable deal. I had been tiny bit acquainted of this your broadcast offered bright clear concept

I couldnÃt refrain from commenting. Well written!

Saved as a favorite, I really like your blog!

I gotta favorite this internet site it seems handy handy

I have been examinating out some of your posts and it’s clever stuff. I will surely bookmark your blog.

Great post, I conceive people should larn a lot from this web site its very user genial.

I have been examinating out many of your articles and i can state pretty nice stuff. I will surely bookmark your blog.

http://maxexch.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=www.fairporn.net/

Servicio tecnico de Frigorificos Binéfar Neveras y Congeladores: Trabajamos las principales marcas de Frigorificos del mercado, con una amplia garantia. Los tecnicos de reparacion de electrodomesticos, llevan consigo todos los repuestos y materiales necesarias para una correcta reparacion de sus electrodomesticos. Nuestros operadores en la centralita le atenderan las 24 horas del dia, todos los dias de la semana durante todo el año. Una vez conozcan su averia enviaran un tecnico a su domicilio que se encargara de realizar la reparacion de su frigorifico.

An impressive share! I have just forwarded this onto a friend who had been conducting a little research on this. And he in fact ordered me breakfast simply because I discovered it for him… lol. So let me reword this…. Thanks for the meal!! But yeah, thanx for spending time to discuss this matter here on your blog.

Aw, this was an extremely good post. Spending some time and actual effort to make a very good articleÖ but what can I sayÖ I procrastinate a lot and don’t seem to get anything done.

http://franschocolates.co/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=www.fairporn.net/

Hi there, I believe your blog might be having web browser compatibility issues. Whenever I look at your website in Safari, it looks fine however, when opening in IE, it has some overlapping issues. I just wanted to provide you with a quick heads up! Besides that, fantastic site!

Hi, i feel that i noticed you visited my web site thus i came to “go back the favor”.I’m trying to find things to enhance my web site!I suppose its ok to make use of a few of your concepts!!

http://personalitytest.org/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=www.fairporn.net/

Un servicio técnico de reparación de electrodomésticos le ayudará a llevar a cabo un mantenimiento correcto de sus electrodomésticos, lo que le ayudará a ahorrar energía y a que sus electrodomésticos duren más. Los electrodomésticos de mayor consumo global son el televisor y el frigorífico, aunque tienen potencias unitarias inferiores a por ejemplo una plancha una lavadora. AEG, Ariston, Artrom, Aspes, Balay, Bru, Candy, Corbero, Cointra, Crolls, Edesa, Electrolux, Fagor, Fleck, Fujitsu, Hoover, Siemens, Bauknecht, Sauber, Indesit, Ignis, Taurus, Daikin, Teka, LG, Carrier, Samsung, Philco, Kenmore, Lynx, New Pol, Superser, Whirpool, Zanussi.

This is the right web site for anyone who wishes to understand this topic. You know a whole lot its almost tough to argue with you (not that I personally would want toÖHaHa). You definitely put a new spin on a topic that’s been written about for years. Excellent stuff, just great!

After I originally left a comment I appear to have clicked on the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and now every time a comment is added I get four emails with the exact same comment. There has to be a way you can remove me from that service? Thanks!

After checking out a number of the blog posts on your web page, I honestly like your way of blogging. I bookmarked it to my bookmark website list and will be checking back soon. Please check out my website too and let me know what you think.

I carry on listening to the newscast lecture about receiving boundless online grant applications so I have been looking around for the most excellent site to get one. Could you advise me please, where could i find some?

An outstanding share! I’ve just forwarded this onto a co-worker who had been doing a little homework on this. And he in fact bought me lunch because I stumbled upon it for him… lol. So let me reword this…. Thank YOU for the meal!! But yeah, thanx for spending time to talk about this subject here on your site.

http://almahmoudia.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=www.fairporn.net/

I went over this internet site and I think you have a lot of good information, saved to favorites (:.

I’m very happy to find this page. I wanted to thank you for ones time just for this wonderful read!! I definitely savored every little bit of it and i also have you book marked to check out new information in your site.

Hi, just required you to know I he added your site to my Google bookmarks due to your layout. But seriously, I believe your internet site has 1 in the freshest theme I??ve came across. It extremely helps make reading your blog significantly easier.

Good post and right to the point. I am not sure if this is truly the best place to ask but do you guys have any thoughts on where to hire some professional writers? Thx 🙂

Great goods from you, man. I’ve understand your stuff previous to and you are just extremely magnificent. I actually like what you have acquired here, certainly like what you are saying and the way in which you say it. You make it entertaining and you still care for to keep it wise. I can not wait to read much more from you. This is actually a terrific website.

I keep listening to the news update talk about getting free online grant applications so I have been looking around for the most excellent site to get one. Could you advise me please, where could i find some?

Hi there! This is my first visit to your blog! We are a collection of volunteers and starting a new project in a community in the same niche. Your blog provided us useful information to work on. You have done a marvellous job!

I like this website so much, saved to favorites. “Respect for the fragility and importance of an individual life is still the mark of an educated man.” by Norman Cousins.

I챠m amazed, I must say. Rarely do I come across a blog that챠s both educative and entertaining, and without a doubt, you’ve hit the nail on the head. The issue is something not enough people are speaking intelligently about. I am very happy I found this during my search for something concerning this.

http://chanproperty.com/__media__/js/netsoltrademark.php?d=www.fairporn.net/

Great post but I was wondering if you could write a litte more on this subject? I’d be very grateful if you could elaborate a little bit more. Appreciate it!

Fantastic goods from you, man. I’ve understand your stuff previous to and you’re just extremely fantastic. I really like what you have acquired here, certainly like what you are stating and the way in which you say it. You make it entertaining and you still care for to keep it wise. I cant wait to read much more from you. This is really a great site.

IÃm amazed, I must say. Rarely do I come across a blog thatÃs both educative and engaging, and without a doubt, you have hit the nail on the head. The issue is something not enough people are speaking intelligently about. I am very happy that I stumbled across this during my search for something relating to this.

Great article. I’m going through some of these issues as well..

The following time I learn a weblog, I hope that it doesnt disappoint me as much as this one. I mean, I do know it was my choice to read, but I truly thought youd have something interesting to say. All I hear is a bunch of whining about one thing that you would repair when you werent too busy in search of attention.

I really like it when people come together and share ideas. Great website, stick with it!

After I originally left a comment I seem to have clicked on the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and from now

on whenever a comment is added I get 4 emails with the exact same comment.

There has to be a means you are able to remove me from that service?

Kudos!

Great website you have here but I was curious about if you knew of any discussion boards that cover the same topics talked about here? I’d really love to be a part of community where I can get advice from other experienced individuals that share the same interest. If you have any recommendations, please let me know. Appreciate it!

I blog often and I really thank you for your content. Your article has truly peaked my interest. I’m going to bookmark your website and keep checking for new details about once a week. I subscribed to your RSS feed as well.

Hello there! This blog post couldnÃt be written much better! Reading through this article reminds me of my previous roommate! He continually kept preaching about this. I will forward this information to him. Pretty sure he will have a good read. Thank you for sharing!

When I originally commented I clicked the “Notify me when new comments are added” checkbox and now each time a comment is added I get three emails with the same comment. Is there any way you can remove people from that service? Thank you!

After I initially commented I appear to have clicked the -Notify me when new comments are added- checkbox and from now on every time a comment is added I receive 4 emails with the exact same comment. There has to be an easy method you are able to remove me from that service? Thanks!

Hey there! This is kind of off topic but I need some help from an established blog. Is it very difficult to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty fast. I’m thinking about setting up my own but I’m not sure where to begin. Do you have any ideas or suggestions? Cheers

I dugg some of you post as I cogitated they were very beneficial extremely helpful

F*ckin’ remarkable issues here. I am very glad to see your article. Thank you so much and i am looking ahead to contact you. Will you kindly drop me a e-mail?

Si busca un servicio ténico de calidad para la reparación de su electrodoméstico siemens, no lo dude: confíe en la seriedad, profesionalidad y rapidez de Ecotenic. Siemens es la empresa fabricante de electrodomésticos de origen alemán con más de 150 años de experiencia. Siemens es una marca líder en innovación tecnológica en la industria de los electrodomésticos, combinando ideas innovadoras, ingeniería de precisión y un diseño moderno atemporal. La mayoría de las lavadoras Siemens incorporan el motor iQdriveTMsin escobillas, eficiente y silencioso.

El máximo beneficio que se logre obtener dependerá de cuánto desee producir, en ese caso, si usted produce una cantidad de piezas baja en un lote es recomendable que utilice una máquina convencional, pero si desea producir una cantidad mediana que ahorre tiempo de operación debe utilizar una máquina de control numérico y, por último, si se desea producir a gran escala es beneficioso recurrir a la automatización de la máquina herramienta a través de un software.

Reparamos todas las averías de cualquier electrodoméstico ARISTON: lavadoras, congeladores, lavavajillas, frigoríficos, hornos. Si alguno de sus electrodomésticos ARISTON tiene alguna avería, no dude en ponerse en contacto con nosotros, uno de nuestros técnicos se pondra en contacto con usted para concretar la hora de visita que mejor le venga. Servicio técnico oficial del fabricante para las marcas LG, Liebherr, Hisense, Sharp, Admiral, Amana, Maytag, Scholtès, etc.

Fresadora : en la fresadora el movimiento de corte lo tiene la herramienta; que se denomina fresa, girando sobre su eje, el movimiento de avance lo tiene la pieza, fijada sobre la mesa de la fresadora que realiza este movimiento. En pequeñas piezas para objetos como pequeños implantes quirúrgicos instrumental médico como pequeñas cánulas incluso cámaras, se requieren equipos muy avanzados CNC cuyo margen de error sea casi inexistente.

Hi there! This is kind of off topic but I need some advice from an established blog. Is it difficult to set up your own blog? I’m not very techincal but I can figure things out pretty fast. I’m thinking about setting up my own but I’m not sure where to begin. Do you have any ideas or suggestions? With thanks

Compre una cafetera cm1 22 hace un mes en media markt se rompio el pocillo y minimoka ni meda markt se hizo cargo de la reparacion por eso minimoka y media markt por pueden cerrar las puertas. Hola, Luis, en este enlace encontrarás todos nuestros Servicios Técnicos Oficiales de la provincia de Valencia para que escojas el que más te convenga y le solicites la pieza que necesitas. Hola, Manuel, seguimos sin entender porqué te han dicho que no había recambios, cuando la pieza que necesitas está disponible y así se le ha informado al Servicio Técnico. Hola Ramón, Para solucionar tu incidencia deberás acudir a un Servicio de Asistencia Técnica.

magnificent publish, very informative. I wonder why the other specialists of this sector don’t realize this. You must proceed your writing. I am confident, you’ve a huge readers’ base already!

También tenemos, en nuestras propias instalaciones, dos técnicos especializados en la reparación de redes y equipos informáticos.

Thank you, I have just been looking for info about this topic for a while and yours is the best I have found out so far. But, what in regards to the conclusion? Are you positive about the source?

En nuestro servicio técnico, disponemos de técnicos con los conocimientos y habilidades técnicas para poder reparar sus electrodomésticos. Las principales averías no son un problema para nuestros profesionales, porque conocemos todas las marcas de lavadoras y sabemos cómo reparar electrodomésticos. Si no es así, se ha de pedir las piezas averiadas y el plazo para reparar se puede alargar hasta dos tres días, pero depende del stock en esos momentos de los recambios y piezas de sustitución. Espero que la próxima vez tengan un poco más de cuidado al contratar al personal.

La dirección de la empresa y los representantes legales de los trabajadores, firmantes de este Convenio acuerdan adherirse al Acuerdo Vasco sobre el Empleo suscrito entre Confebask y las Centrales Sindicales ELA, , UGT y LAB el pasado 15 de enero de 1999.

fantastic post, very informative. I’m wondering why

the opposite experts of this sector don’t understand this.

You should proceed your writing. I am sure, you have a huge readers’ base already!

Mediante esta opción tras simular el arranque de material, se pueden observar las zonas más conflictivas en las que queda sobrespesor en las que se ha mecanizado más de lo deseado. Además, gracias a nuestros tornos CNC estamos en condiciones de fabricar las piezas y ejes que necesites.

Just bookmarked this blog post as I have actually found it fairly valuable.

Nuestra empresa, con más de 24 anos de experiencia, respeta y sigue las normas de calidad establecidas por Corbero para las reparaciones de su Frigorificos Corbero, ya que creemos que es la mejor manera de satisfacer al cliente tanto técnica como económicamente, al tiempo que prolongamos la vida de la Frigorificos utilizando recambios originales Corbero.

MIPESA GRUPO EMPRESARIAL, engloba diversas industrias auxiliares de mecanizado, poniendo a su disposición desde nuestros talleres, servicios de fabricación integrales, como mecanizado por arranque de viruta, corte láser, punzonado, plegado, soldadura y montaje de maquinaria y conjuntos. El centro de mecanizado CNC PRO-MASTER 7225 ofrece a la empresa un innovador diseño de máquina con un espectro de servicio adaptable a cualquier situación operativa, y todo ello con cinco ejes de interpolación. MECANIZADOS CNC Somos una empresa que brinda servicios con maquinarias de altatecnología CNC “MECANIZADOS CNC” a la industria en general, mecanizado de piezas enserie en Tornos CNC y Centros Mecanizados CNC.

El programa Renovate, que promueve el cambio de electrodomésticos por productos similares pero de menor consumo de electricidad, se extendió a 10 nuevas localidades de la provincia de Buenos Aires, informó hoy el Ministerio de Economía. Siemens revoluciona el mundo del cuidado de la ropa con las nuevas lavadoras masterClass que destacan por su diseño, con nuevo display TFT de alta definición y máximo contraste. Este sistema pretende actuar sobre las dos Fuentes que producen más ruido, el motor y el aire.

La dirección de la empresa y los representantes legales de los trabajadores, firmantes de este Convenio acuerdan adherirse al Acuerdo Vasco sobre el Empleo suscrito entre Confebask y las Centrales Sindicales ELA, , UGT y LAB el pasado 15 de enero de 1999.

Asimismo, nuestro hotel alberga cafetería, restaurante, bar, aparcamiento, servicio de lavandería, servicio de habitaciones y 19 salas de conferencias y banquetes para diferentes eventos de hasta 00 participantes. Con esta exposición se consiguen reunir por primera vez en España los 14 lienzos que conforman las Visiones de España de Joaquín Sorolla, que pintó por encargo de la Hispanic Society de Nueva York.

Informamos que no atendemos averías de aparatos en periodo de garantía, no somos servicio técnico oficial Siemens en Navalcarnero, sino que ofrecemos nuestros servicios para su reparación. Informe acerca de nuestros servicios: Servicio tecnico Siemens Vizcaya, Mantenimiento Siemens Vizcaya, Reparación Siemens Vizcaya, e Instalacion Siemens Vizcaya Si desea más información, puede llamarnos sin compromiso y le resolveremos cualquier duda.

Having read this I believed it was rather enlightening.

I appreciate you finding the time and effort to

put this short article together. I once again find myself spending a

significant amount of time both reading and commenting.

But so what, it was still worth it!

Hi! I’ve been reading your blog for a while now and finally got the bravery to go ahead

and give you a shout out from Dallas Tx! Just wanted to tell you keep up the fantastic job!

Excellent post. I used to be checking constantly this blog and I am inspired! Very useful information particularly the last part 🙂 I deal with such information much. I was looking for this particular information for a very lengthy time. Thank you and best of luck.

Reparación Hornos Pinto, servicio técnico de reparación hornos Pinto está especializado en solucionar todas las averías que se presenten, tales como: No enciende el horno, no calienta, hace mucho ruido el electrodoméstico, saltan los plomos diferencial, no calienta una parte del horno, no funciona el temporizador, no funciona el selector de temperatura, no calienta la resistencia, botonera mal, sale código de error, se queda bloqueado.

Somos una empresa dedicada a la fabricación de piezas y a la reparación y mantenimiento de maquinaria, utensilios y construcciones mecánicas. Suministros Industriales y Servicio de Asistencia Técnica SAT. Esta página utiliza cookies propias y de terceros para mejorar nuestros servicios y así facilitar tu navegación.

Hey very nice site!! Man .. Excellent .. Amazing .. I’ll bookmark your website and take the feeds also…I am happy to find numerous useful information here in the post, we need develop more techniques in this regard, thanks for sharing. . . . . .

Servicio Técnico lavadoras Siemens Pozuelo de Alarcón, Servicio Técnico lavavajillas Siemens Pozuelo de Alarcón, Servicio Técnico vitrocerámicas Siemens Pozuelo de Alarcón, Servicio Técnico secadoras Siemens Pozuelo de Alarcón, Servicio Técnico neveras Siemens Pozuelo de Alarcón, Servicio Técnico frigoríficos Siemens Pozuelo de Alarcón. Estamos especializados en la reparación y mantenimiento de los Electrodomésticos de los más prestigiosos fabricantes nacionales y de importación. Asi mismo el personal que forma nuestro equipo humano de técnicos se someten periodicamente a formación continua en cursos de reciclaje.

But a smiling visitant here to share the love (:, btw outstanding style and design. “Individuals may form communities, but it is institutions alone that can create a nation.” by Benjamin Disraeli.

I truly enjoy examining on this website, it holds fantastic blog posts. “Beware lest in your anxiety to avoid war you obtain a master.” by Demosthenes.

esenyurt escort bayanar bu sitede üstelik hepsi ücretsiz…

Es mucho mejor seguir tu instinto que dejarte aconsejar, ahora no dejo de preguntarme que tal habría sido aquel BOSCH de 37db que era un poco más caro pero tal vez más silencioso. Hace 3 años gracias a este blog compré un TEKA CB385, combi y cíclico con 39 db, estoy muy contenta con él pero parece que ahora lo han descatalogado y yo necesito comprar otro para otra vivienda. Gracias a los mas de 15 centros de Asistencia tecnica Balay de que disponemos en Barcelona, Provincia y Girona le desplazamos un técnico a su domicilio en el mismo dia de su llamada.

El C tendrá una suspensión muy sofisticada (hay gente a la que no le gusta, segun comentan en este mismo portal, en la prueba del clase E), pero en los demas aspectos mecanicos es del montón directamente del furgon de cola (en motores asi era, hasta que le han puesto el 3 litros diesel). La flexibilidad está pilotada de manera independiente con 2 estados en cada eje; autoadaptativa en función del estilo de conducción, del perfil de la carretera y de la velocidad. Respecto a los dueños de los Mercedes, estos me hacen también por lo general mucha gracia.

Todo lo necesario para convertir ROBODRILL en una máquina CNC de 5 ejes son algunas piezas de hardware adicionales; el control simultáneo para 5 ejes y los requisitos relativos al CNC (como la indexación y el funcionamiento simultáneo) ya están incorporados en este último.

Una vez pintado, se enviará al Departamento de Pruebas de Calidad para el control por detección 3D. Una vez que todo está revisado y conforme se hacen fotos a los prototipos y se le envían al cliente para su aprobación final, como fase previa al envío de los prototipos.

Ellos saben que los trabajos tiene que estar muy bien acabados, que son trabajos de mucha precisión, de muchísima calidad de acabado superficial y si se parte una herramienta se queda clavada en una ranura de ancho de 0,8mm ya no se puede sacar. Para iniciar su producción ha sido necesario instalar nuevas máquinas de producción, adaptar las líneas de fabricación y realizar los ensayos necesarios que garanticen los estándares medioambientales, seguridad y calidad de la compañía.

Por la noche tampoco para.Necesito saber si hay más personas que le pase lo mismo porque el servicio técnico alega que estos aparatos funcionan así. Me he comprado un frigorifico fagor sistema no normal que al cerrarse se este oyendo siempre ruido de salir aire. Yo tengo un combi Balay (a los efectos igual que los Siemens Bosch, pues el fabricante es el mismo) y se me hacía mucho en el suelo del congelador. Hay preguntas por fagor que hace hielo el evaporador me consejo por experiencia cambiar la resetencia de descongelacion la de abajo le que va rodeando a la bandeja de alumenio de desague-.

Does your website have a contact page? I’m having a tough time locating it but, I’d like to shoot you an email. I’ve got some creative ideas for your blog you might be interested in hearing. Either way, great site and I look forward to seeing it expand over time.

Reparacion de aire acondicionado en Madrid, en la compañía, nos dedicamos a la reparaciones cointra de aire acondicionado, instalación y también efectuamos el mantenimiento de aire acondicionado familiar y también industrial, hacemos reparaciones de aparatos de aire acondicionado por conductos, reparación de fugas de gas y cargas de gas.

Pieza especial mecanizado por decoletaje en acero © Kuzu, S.L. 94. Casquillo especial mecanizado por decoletaje en acero © Kuzu, S.L. El mecanizado CNC de giro rápido es ideal para la creación de prototipos, modelos de pruebas de forma y ajuste, plantillas de guías y accesorios, así como para componentes funcionales de productos terminados.

Un toque caribeño con las potentes máquinas de HOLZ-HER. Desde su fundación, su actividad principal ha sido la fabricación de engranajes y derivados, si bien se realizan todo tipo de trabajos de mecanizado cuyas especificaciones son suministradas por los clientes.

En España Eutelsat y sobre todo Astra e Hispasat a través de empresas pioneras como Gesico (Gestión de Sistemas de Comunicación) explotan el negocio de la banda ancha para dar acceso bidireccional a Internet y han conseguido dar un importante salto cualitativo con la aplicación de nuevas tecnologías vía satélite mucho más óptimas y eficaces que el ADSL.

Nuestra tecnología de mecanizados CNC da cabida tanto a prototipos de EPS sencillos, habituales en la industria, como a prototipado 3D de superficies complejas, ofreciendo así una alternativa real a la impresión 3D al sinterizado. Nuestro compromiso, ofrecer a nuestros clientes un trabajo de precisión, de gran calidad y unos precios competitivos.

Entre las lesiones frecuentes en los talleres de mecanizado se encuentran partículas de material en los ojos, cortaduras, y lesiones por atoramiento y aplastamiento en máquinas. Este tipo de negocio no suele disponer de ingresos recurrentes como tales, pero como todos, si el cliente está satisfecho reclamará más servicios y productos en el futuro.

No me creo que sean tan informales y no se pueda conseguir por ningún medio que nos atiendan, y al parecer da igual que sea de Granada, Córdoba de donde sea, impresentables en general. Tras mandarles una reclamación en impreso oficial via postal certificado y acuse de recibo he conseguido el abono de dicha factura. Hola, se me ha roto una goma de mi horno fagor que se cambia en un minuto (ni mas ni menos) y me piden 2 euros. Le digo que no me la cambie, y me ha cobrado 35 euros por desplazamiento, siendo que estan muy cerca de mi casa NUNCA MAS NADA DE FAGOR.

Al final del libro vienen unos anexos con una serie de tablas y datos de gran interés para diseñar, instalar y mantener las instalaciones frigoríficas (tablas, diagramas, legislación, recuperación de gases refrigerantes, reducción de emisiones, símbolos, unidades, etc.). En definitiva es un libro fundamental para todo el sector del frío, la refrigeración, la climatización y en definitiva para todo el sector de las instalaciones relacionadas con el frío y calor.

Profesional CON EXPERIENCIA en compras y ventas al por mayor, que conozca el mercado nacional de tecnología y electrónica. Búsqueda orientada a personas de ambos sexos de entre 20 y 30 años de edad para tareas operativas en oficina de cargas de Línea Aérea internacional en el AEROPUERTO DE QUITO – Tababela. De preferencia con experiencia en el actividades similares relacionadas con atención al cliente.

Miles de policías se han manifestado hoy, bajo la lluvia, en Madrid, convocados por el Sindicato Unificado de Policía (SUP), mayoritario en el cuerpo, para trasladar al Ministerio del Interior su malestar por los recortes salariales a los agentes. Las derechas han sido siempre las que se han presentado como las grandes defensoras de la patria, defensa que requiere los máximos sacrificios de los que están a su servicio. Y el servicio técnico no esta mal la verdad y eso que estaba acojonado por lo que se leia a veces.

Además, los estudiantes pactaron con los Ferrocarriles de la Generalitat de Catalunya (FGC), para que ningún tren se detenga en la estación del campus hasta las 11:00 horas, como ha ocurrido en otras ocasiones en las que habido movilizaciones de protesta, para evitar una afectación general de las líneas. En la Universidad Autónoma de Madrid se han paralizado una gran parte de las clases y los estudiantes han marchado por todo el campus hasta el rectorado.

Requerimos experiencia previa en el rubro y en la posición, perfil pro-activo, buena predisposición para la atención al cliente y capacidad para el trabajo en equipo. Nos encontramos en la búsqueda de administrativos de mantenimiento, con perfile y conocimiento técnico de las áreas que tendrán en supervisión. Importante Empresa de Servicios de Salud de la ciudad de Mar del Plata busca incorporar personal para atención al público. Se solicita un técnico para realizar tareas de ventas y asesoramiento en una empresa metalúrgica para productos relacionados con hidráulica y neumática.

Todas nuestras piezas tienen mucha precisión y están diseñadas en alta calidad. Lo que se hace es que se realiza un movimiento de corte lineal con la pieza fijada sobre el cepillo. Calibración de máquinas herramienta. Desde nuestro centro de mecanizado realizamos todo tipo de piezas, para las industrias del automóvil, ferroviaria, naval, hidráulica, fabricantes de maquinaria y muchas más.

Las herramientas de corte. Maquinaria de última generación seguido de años de experiencia en diferentes sectores. Descubra el potencial de la serie PRO-MASTER Los centros de mecanizado de la serie PRO-MASTER se distinguen por su sólido diseño y su máxima flexibilidad.

Los servicios ofrecidos por nuestro Servicio Tecnico no estan oficialmente avalados certificados por ningun fabricante u organizacion oficial.

I enjoy reading through an article that will make men and women think. Also, thanks for permitting me to comment!

Tanto para torneado como fresado, etc., contamos con máquinas CNC. De desbaste (eliminación de mucho material con poca precisión; proceso intermedio) y de acabado (eliminación de poco material con mucha precisión; proceso final) y super pulidos. Puede cortar eficientemente materiales en pedazos pequeños al mismo tiempo que utiliza un conjunto diversificado de herramientas.

Todo un extenso conjunto de posibilidades por un costo económico a través de nuestro servicio técnico Bosch Vilassar de Dalt. Todo un extenso conjunto de posibilidades por un costo económico a través de nuestro servicio técnico Bosch Vilassar de Mar. Todo un extenso conjunto de posibilidades por un costo económico a través de nuestro servicio técnico Bosch Torelló. Todo un extenso conjunto de posibilidades por un costo económico a través de nuestro servicio técnico Bosch Vallirana. Todo un extenso conjunto de posibilidades por un costo económico a través de nuestro servicio técnico Bosch Vic. Todo un extenso conjunto de posibilidades por un costo económico a través de nuestro servicio técnico Bosch Viladecans.

My wife and i ended up being so more than happy that Chris managed to carry out his investigations through the entire precious recommendations he had using your site. It’s not at all simplistic to just find yourself making a gift of concepts that many some people could have been making money from. And we also do understand we have you to appreciate for that. The explanations you have made, the easy website menu, the friendships you can help engender – it’s all wonderful, and it is aiding our son and the family know that the concept is cool, which is truly important. Thank you for all the pieces!

Total que en un tono lo más impertinente posible me dice que en cuanto la tenga que les llame para ver si está todo correcto, le digo que no pienso llamarles para comentarles mi vida que si quiere algo que me llame ella, que ya he puesto la denuncia en consumo y que a partir de ahora se encargan ellos, pero que lo que me interesa como le he dicho en los mails mil veces es el cambio de terminal que me diga que me lo deniegan que estoy grabando la conversación para adjuntarla a la denuncia.

I like this blog its a master peace ! Glad I noticed this on google .

Contamos con un equipo de trabajo experimentado capaz de ayudar a cada uno de nuestros clientes en las necesidades que puedan tener. La dilatada experiencia en el sector y el personal altamente cualificado que forma nuestro equipo, nos permite ofrecer un servicio completo a nuestros clientes.

I appreciate the manner you have ended this post …

En los últimos años el concepto de lo vintage se ha propagado como la espuma. El técnico fue relativamente rápido, pero como no tiene arreglo (es muy caro), es donde empiezan los problemas. Estoy en tu misma situación, en julio suscribí un seguro con la compañia Domestic & General que cubria la reparación inicial y seguro durante un año de todas las reparaciones y susutitución por un lavavajillas por otro de igual valor si no se podia reparar. Con la primera reparación no tuve ningún problema, pero pasados seis meses se vuelve a estropear, lleva casi tres meses reparandose y no se nada más. Una media de dos averías al año, lo ´se, el plasma de LG es una castaña brutal, pero la garantía de General es una mezcla del PP+PSOE+Diarrea de perro sato.

You have actually covered this subject expertly.

Conscientes de las exigencias del sector, apostamos por la excelencia, dotándonos de medios técnicos, infraestructuras y un equipo humano competente con amplia experiencia, capacidad de adaptación e innovación. En el caso de que se opte por un Servicio de Prevención ajeno entregará tanto a los Delegados de Prevención como al Comité de Seguridad y Salud Laboral información sobre las características técnicas de dicho concierto.

Llámenos si su electrodomesticos no funciona, nuestros técnicos elaborarán un diagnóstico de su electrodomesticos y su avería con absoluta franqueza, le ofrecerán la mejor solución para la restauración de su electrodomesticos al funcionamiento que tenía cuando lo compró. Su electrodomesticos es un electrodoméstico fundamental en la casa, por ello, cuando se estropea, usted necesita el servicio más rápido y profesional posible. Cuando se estropea su electrodomesticos usted se enfurece y se impacienta porque supone un trastorno en su vida cotidiana y en su economía.

El proceso comienza eliminando gran parte del material de una manera poco precisa (desbaste) continuando con un desarrollo final mucho más minucioso (acabado). Si quieres saber más sobre nosotros y los tipos de mecanizado y fabricación de maquinaria que realizamos, visita nuestra web y conoce todos los servicios que tenemos para tu empresa.

Disponemos de centros de mecanizado de 3, 4 y 5 ejes, tornos de doble cabezal, doble torreta y eje Y. Con una capacidad de mecanizado en piezas de hasta 5 metros en longitudinal y en piezas de revolución hasta 400 mm de diámetro, en distintos tipos de materiales como titanio, aluminio, inconel, ph y poliamida entre otros, nos distinguimos por cumplir rigurosamente con los plazos de entrega.

Será posible acumular, igualmente, saldos negativos en épocas de baja actividad con el límite de 9 horas al año compensando la diferencia sobre la jornada laboral en el primer trimestre del año siguiente. El compromiso mutuo entre cada Técnico y la Empresa para la prestación del Servicio de emergencia estará avalado por un escrito específico del evento con una duración de un año. Las horas activas durante el Servicio de emergencia, a ser posible, no superarán de forma sistemática el 25 del total de horas pasivas correspondientes.

Vérselas negras.

Creo sinceramente que la calidad de una marca no se mide solo por el buen funcionamiento de sus electrodomésticos sino también por la calidad de asistencia humana cuando te encuentras ante situaciones de tanta impotencia como verte sin nevera ni congelador durante cinco días y la comida poniéndose mala. Ademas , no sirven repuestos a otras empresas , por lo que te ves obligado a llamarles a ellos para que te vengan a casa a atracar. Deja de funcionar y viene el técnico y dice que es porque el enchufe está mal y por eso no conectan bien las dos fases (?). De esto hace 12 días y en el servicio técnico no hay forma de hablar con ellos. Posterior a la reparación de la frigorífico, tendrá una garantía de TRES MESES.

HERCA S.L es una empresa enmarcada en el sector industrial, dentro del ámbito del mecanizado, rectificado, fresado y roscado. En Mecanizados velamos por la calidad de vida de nuestro equipo humano, generando puestos de trabajo equilibrados, fomentando la profesionalidad y motivando la implicación y el espíritu de equipo dentro de la organización. Mecanizados, proyectos, soldadura especial, fabricación y reparaciones de maquinaria, repuestos.

Apelo pues a su profesionalidad y les invito a ponerse en contacto con Jose Antonio, de Cocinas Campos en Córdoba, quien también les podrá confirmar lo que les digo, pues ha sido normalmente a quien hemos llamado antes incluso de dirigirnos a su servicio técnico, dada la confianza que tenemos en ellos. Buenas tardes, les escribo con motivo de emitir una queja, ya que estoy indignada con el servicio técnico de Electrolux en Logroño. A mediados de julio se rompe el módulo de potencia de mi aspirador, ya que tiene dos años de garantía y cumplía en septiembre, sobre finales de julio de este mismo año lo llevo al servicio técnico, sito en Av. xxxxxxxxx, en Logroño.

En cualquier instalación de servicios climatización, se utilizan máquinas para mover los fluidos de trabajo y por tanto el conocimiento de las bombas, ventiladores y compresores permitirá la elección correcta de las mismas para que los sistemas trabajen correctamente y con un máximo aprovechamiento energético. Está adaptado al cumplimiento del RITE y todo se expone de forma clara y práctica, siendo una herramienta muy útil para el profesional, técnico y estudiante del tema. A partir de la instalación de 3 tipos de equipos de aire acondicionado, según tamaño, potencia, equipo, etc., se desarrolla un manual eminentemente práctico para la instalación de estos equipos y su mantenimiento.

Con intención de evaluar la capacidad del modelo de distorsiones para el cálculo del estado de placas tras procesos de mecanizado, se han llevado a cabo el mecanizado de dos piezas de geometría análoga que pudieran mostrar curvaturas finales considerablemente diferentes.

Hey there! I simply want to offer you a big thumbs up for the excellent information you have here on this post. I’ll be returning to your website for more soon.

https://www.kiva.org/lender/freddy1120

Contamos con personal cualificado con más de 25 años de experiencia en el mecanizado de precisión y máquinas herramienta de control numérico torno y fresa. Buscamos la satisfacción de nuestros clientes y para responder a sus necesidades contamos con la tecnología más avanzada así como máquinas de gran precisión y productividad, que se complementan con medios de verificación de última generación.

Nuestra actividad se basa en el decoletaje de precisión y mecanizado de piezas especiales, siempre bajo especificaciones del cliente, a quien también asesoramos para ofrecerle nuestra experiencia de cara a la solución de sus problemas, contando con más de 15 años de experiencia y presencia en el mercado.